Social Proof: Why does it matter so much?

Is social proof just a social construct or is it embeddedin our evolutionary genes? How do businesses leverage social proof and what are its implications?

Welcome to Issue #6 of Market Curve - a weekly newsletter exploring the intersection of marketing with consumer psychology and behavioral economics. Market Curve offers marketers and founders a different perspective on how to better understand their customers - one that is rooted in science.

Thank you for subscribing, and please tell a few friends if you’d like!

— Shounak

Social proof is based on two elements: (a) Uncertainty and (b) Similarity. Let’s understand each concept and how it plays into the customer buying decision.

Uncertainty is scary for us. We find ways to avoid it or find ways of dealing with it. Social proof is an example of the latter.

We are primed to look to others for help when we enter unchartered territory. As explorers and hunter-gatherers, our brains are look for patterns to decode the mystery accompanying uncertainty.

The greater the uncertainty, the more we tend to gravitate towards social proof.

We assume that people around us have all the answers we are looking for. Maybe they can share their wisdom with us and can rid us of our predicaments. This is where testimonials or endorsements are so powerful.

It becomes even more powerful when the validation comes from someone we admire and who we perceive to be better placed to show us the way. Take for example Naval.

Naval’s seal of approval is all it takes for a book to become a best-seller overnight to the folks within Silicon Valley. Naval is perceived as this person whose recommendations, if followed, can change one's life.

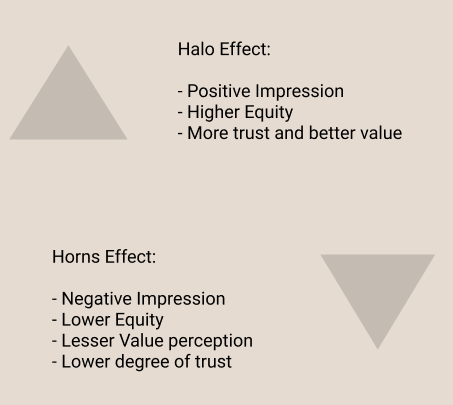

This is due to a phenomenon known by psychologists as the ‘halo and horns effect’ which posits that we see a product/service as more desirable if it is associated with someone we like. On a subconscious level, we imagine their good qualities rubbing off on the item advertised.

Likewise, if we wish to be like someone, we may think anything they endorse will make us more like them.

The higher the social status and perceived value, the greater weight his social proof carries.

Let’s take this narrative a little further. Let’s say Naval endorses the book “Navalmanack” by Jorgensen. And it blows up on Twitter. As a result, let’s say 10 million have ended up buying the book which gives rise to an interesting phenomenon.

The greater the number of people, the greater is the social proof and greater is its persuasive value. This is known as the multiple source effect.

Social proof is a flame to the human mind moth,

and it leaves a fire trail of destruction across the path of enough.—Will Jelbert, The Happiness Animal.

Social proof is powerful because it allows us to employ mental shortcuts that we can use to quickly make decisions. But at times, it poses more harm than good.

Here’s an example.

I am subscribed to a newsletter from a freelancer. He was selling an e-book which he had not started writing but was opening up for pre-orders. The people who would pre-order his book would get a fat discount compared to people who bought it after the book was written. Not only that, if someone gave him a video testimonial or written testimonial, he would give an additional 10% discount which means people are incentivized to give raving reviews even if they haven't read the book. And it's not like they can give bad reviews either - they were paid to write good reviews.

Do this for 10 people and you have 10 testimonials from people before the book is even published. And people will look at these people saying magnificent things and follow the herd mentality and say "I want this too"! This is a classic example of manufacturing desire. The customer didn’t know he wanted it but seeing his own peers singing praises, he succumbed to the herd mentality.

This will be even more powerful if people of a similar tribe endorse the book.

This is similar to what claquers used to do back in the 16th century. A claque consisted of a group of professional applauders, positioned in theaters or opera houses.Their job was to applaud a performance, encouraging others to do the same. Social proof meant that once a few people began to applaud, the rest did the same.

This is the same in the case of canned laughter in television shows. This is especially true for content that is poor in quality. The laughter is made to artificially invoke the feeling of mirth and make the audience feel that it is indeed a funny line. Maybe it is the case with mediocre products too. Is the number of testimonials inversely proportional to the quality of the product? Do they have to show off more in order to hide their mediocrity?

There is evidence to support this claim. For instance, most of the newsletters I subscribe to refurbish content from other places. It's hardly original. Very few are and those are the ones who ironically fly under the radar.

Even while researching this piece, I found the same examples and the same stories cited across 7 different websites. All that changed was the layout and structure.

But there are exceptions to the rule in both cases.

Social proof acts on the assumption that the collective wisdom is greater than the individual. Democracy is built on this notion. But like someone said - "Democracy is only the counting heads, not what's in it". Maybe the same could be said for social proof.

Thank you so much for reading! If you want to get in touch, you can respond directly to this email or reach out on Twitter or Email. Always excited to meet like-minded humans!

Until next week!

— Shounak.